(I wrote this blog post a couple of months ago, but it's still quite relevant.)

Hi, I'm Daniel! I work in OzLabs, part of IBM's Australian Development Labs. Recently, I've been assigned to the CAPI project, and I've been given the opportunity to give you an idea of what this is, and what I'll be up to in the future!

What even is CAPI?

To help you understand CAPI, think back to the time before computers. We had a variety of machines: machines to build things, to check things, to count things, but they were all specialised --- good at one and only one thing.

Specialised machines, while great at their intended task, are really expensive to develop. Not only that, it's often impossible to change how they operate, even in very small ways.

Computer processors, on the other hand, are generalists. They are cheap. They can do a lot of things. If you can break a task down into simple steps, it's easy to get them to do it. The trade-off is that computer processors are incredibly inefficient at everything.

Now imagine, if you will, that a specialised machine is a highly trained and experienced professional, a computer processor is a hungover university student.

Over the years, we've tried lots of things to make student faster. Firstly, we gave the student lots of caffeine to make them go as fast as they can. That worked for a while, but you can only give someone so much caffeine before they become unreliable. Then we tried teaming the student up with another student, so they can do two things at once. That worked, so we added more and more students. Unfortunately, lots of tasks can only be done by one person at a time, and team-work is complicated to co-ordinate. We've also recently noticed that some tasks come up often, so we've given them some tools for those specific tasks. Sadly, the tools are only useful for those specific situations.

Sometimes, what you really need is a professional.

However, there are a few difficulties in getting a professional to work with uni students. They don't speak the same way; they don't think the same way, and they don't work the same way. You need to teach the uni students how to work with the professional, and vice versa.

Previously, developing this interface – this connection between a generalist processor and a specialist machine – has been particularly difficult. The interface between processors and these specialised machines – known as accelerators – has also tended to suffer from bottlenecks and inefficiencies.

This is the problem CAPI solves. CAPI provides a simpler and more optimised way to interface specialised hardware accelerators with IBM's most recent line of processors, POWER8. It's a common 'language' that the processor and the accelerator talk, that makes it much easier to build the hardware side and easier to program the software side. In our Canberra lab, we're working primarily on the operating system side of this. We are working with some external companies who are building CAPI devices and the optimised software products which use them.

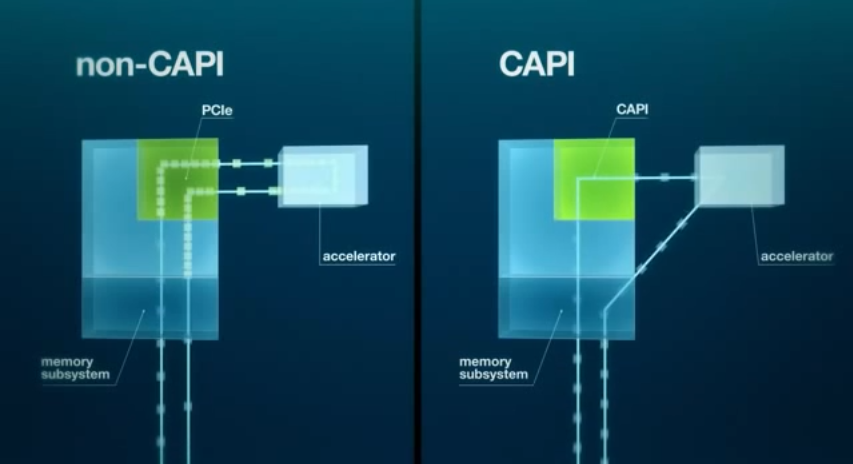

From a technical point of view, CAPI provides coherent access to system memory and processor caches, eliminating a major bottleneck in using external devices as accelerators. This is illustrated really well by the following graphic from an IBM promotional video. In the non-CAPI case, you can see there's a lot of data (the little boxes) stalled in the PCIe subsystem, whereas with CAPI, the accelerator has direct access to the memory subsystem, which makes everything go faster.

Uses of CAPI

CAPI technology is already powering a few really cool products.

Firstly, we have an implementation of Redis that sits on top of flash storage connected over CAPI. Or, to take out the buzzwords, CAPI lets us do really, really fast NoSQL databases. There's a video online giving more details.

Secondly, our partner Mellanox is using CAPI to make network cards that run at speeds of up to 100Gb/s.

CAPI is also part of IBM's OpenPOWER initiative, where we're trying to grow a community of companies around our POWER system designs. So in many ways, CAPI is both a really cool technology, and a brand new ecosystem that we're growing here in the Canberra labs. It's very cool to be a part of!