(This was published in an internal technical journal last week, and is now being published here. If you already know what Docker is, feel free to skim the first half.)

Docker seems to be the flavour of the month in IT. Most attention is focussed on using Docker for the deployment of production services. But that's not all Docker is good for. Let's explore Docker, and two ways I use it as a software developer.

Docker: what is it?

Docker is essentially a set of tools to deal with containers and images.

To make up an artificial example, say you are developing a web app. You first build an image: a file system which contains the app, and some associated metadata. The app has to run on something, so you also install things like Python or Ruby and all the necessary libraries, usually by installing a minimal Ubuntu and any necessary packages.1 You then run the image inside an isolated environment called a container.

You can have multiple containers running the same image, (for example, your web app running across a fleet of servers) and the containers don't affect each other. Why? Because Docker is designed around the concept of immutability. Containers can write to the image they are running, but the changes are specific to that container, and aren't preserved beyond the life of the container.2 Indeed, once built, images can't be changed at all, only rebuilt from scratch.

However, as well as enabling you to easily run multiple copies, another upshot of immutability is that if your web app allows you to upload photos, and you restart the container, your photos will be gone. Your web app needs to be designed to store all of the data outside of the container, sending it to a dedicated database or object store of some sort.

Making your application Docker friendly is significantly more work than just spinning up a virtual machine and installing stuff. So what does all this extra work get you? Three main things: isolation, control and, as mentioned, immutability.

Isolation makes containers easy to migrate and deploy, and easy to update. Once an image is built, it can be copied to another system and launched. Isolation also makes it easy to update software your app depends on: you rebuild the image with software updates, and then just deploy it. You don't have to worry about service A relying on version X of a library while service B depends on version Y; it's all self contained.

Immutability also helps with upgrades, especially when deploying them across multiple servers. Normally, you would upgrade your app on each server, and have to make sure that every server gets all the same sets of updates. With Docker, you don't upgrade a running container. Instead, you rebuild your Docker image and re-deploy it, and you then know that the same version of everything is running everywhere. This immutability also guards against the situation where you have a number of different servers that are all special snowflakes with their own little tweaks, and you end up with a fractal of complexity.

Finally, Docker offers a lot of control over containers, and for a low performance penalty. Docker containers can have their CPU, memory and network controlled easily, without the overhead of a full virtual machine. This makes it an attractive solution for running untrusted executables.3

As an aside: despite the hype, very little of this is actually particularly new. Isolation and control are not new problems. All Unixes, including Linux, support 'chroots'. The name comes from “change root”: the system call changes the processes idea of what the file system root is, making it impossible for it to access things outside of the new designated root directory. FreeBSD has jails, which are more powerful, Solaris has Zones, and AIX has WPARs. Chroots are fast and low overhead. However, they offer much lower ability to control the use of system resources. At the other end of the scale, virtual machines (which have been around since ancient IBM mainframes) offer isolation much better than Docker, but with a greater performance hit.

Similarly, immutability isn't really new: Heroku and AWS Spot Instances are both built around the model that you get resources in a known, consistent state when you start, but in both cases your changes won't persist. In the development world, modern CI systems like Travis CI also have this immutable or disposable model – and this was originally built on VMs. Indeed, with a little bit of extra work, both chroots and VMs can give the same immutability properties that Docker gives.

The control properties that Docker provides are largely as a result of leveraging some Linux kernel concepts, most notably something called namespaces.

What Docker does well is not something novel, but the engineering feat of bringing together fine-grained control, isolation and immutability, and – importantly – a tool-chain that is easier to use than any of the alternatives. Docker's tool-chain eases a lot of pain points with regards to building containers: it's vastly simpler than chroots, and easier to customise than most VM setups. Docker also has a number of engineering tricks to reduce the disk space overhead of isolation.

So, to summarise: Docker provides a toolkit for isolated, immutable, finely controlled containers to run executables and services.

Docker in development: why?

I don't run network services at work; I do performance work. So how do I use Docker?

There are two things I do with Docker: I build PHP 5, and do performance regression testing on PHP 7. They're good case studies of how isolation and immutability provide real benefits in development and testing, and how the Docker tool chain makes life a lot nicer that previous solutions.

PHP 5 builds

I use the isolation that Docker provides to make building PHP 5 easier. PHP 5 depends on an old version of Bison, version 2. Ubuntu and Debian long since moved to version 3. There are a few ways I could have solved this:

- I could just install the old version directly on my system in

/usr/local/, and hope everything still works and nothing else picks up Bison 2 when it needs Bison 3. Or I could install it somewhere else and remember to change my path correctly before I build PHP 5. - I could roll a chroot by hand. Even with tools like debootstrap and schroot, working in chroots is a painful process.

- I could spin up a virtual machine on one of our development boxes and install the old version on that. That feels like overkill: why should I need to run an entire operating system? Why should I need to copy my source tree over the network to build it?

Docker makes it easy to have a self-contained environment that has Bison 2 built from source, and to build my latest source tree in that environment. Why is Docker so much easier?

Firstly, Docker allows me to base my container on an existing container, and there's an online library of containers to build from.4 This means I don't have to roll a base image with debootstrap or the RHEL/CentOS/Fedora equivalent.

Secondly, unlike a chroot build process, which ultimately is just copying files around, a docker build process includes the ability to both copy files from the host and run commands in the context of the image. This is defined in a file called a Dockerfile, and is kicked off by a single command: docker build.

So, my PHP 5 build container loads an Ubuntu Vivid base container, uses apt-get to install the compiler, tool-chain and headers required to build PHP 5, then installs old bison from source, copies in the PHP source tree, and builds it. The vast majority of this process – the installation of the compiler, headers and bison, can be cached, so they don't have to be downloaded each time. And once the container finishes building, I have a fully built PHP interpreter ready for me to interact with.

I do, at the moment, rebuild PHP 5 from scratch each time. This is a bit sub-optimal from a performance point of view. I could alleviate this with a Docker volume, which is a way of sharing data persistently between a host and a guest, but I haven't been sufficiently bothered by the speed yet. However, Docker volumes are also quite fiddly, leading to the development of tools like docker compose to deal with them. They also are prone to subtle and difficult to debug permission issues.

PHP 7 performance regression testing

The second thing I use docker for takes advantage of the throwaway nature of docker environments to prevent cross-contamination.

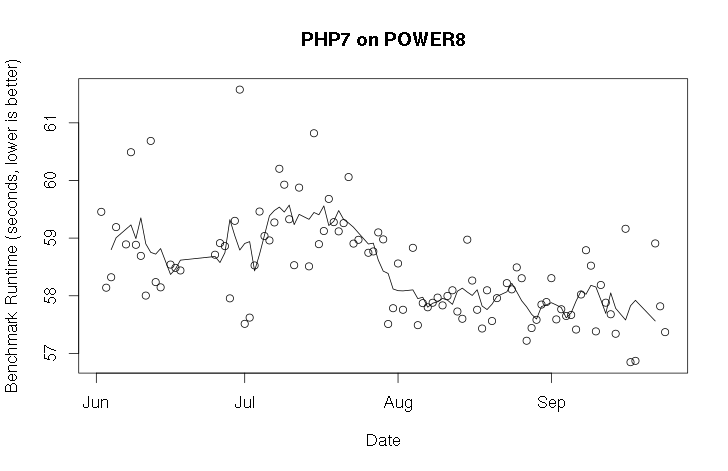

PHP 7 is the next big version of PHP, slated to be released quite soon. I care about how that runs on POWER, and I preferably want to know if it suddenly deteriorates (or improves!). I use Docker to build a container with a daily build of PHP 7, and then I run a benchmark in it. This doesn't give me a particularly meaningful absolute number, but it allows me to track progress over time. Building it inside of Docker means that I can be sure that nothing from old runs persists into new runs, thus giving me more reliable data. However, because I do want the timing data I collect to persist, I send it out of the container over the network.

I've now been collecting this data for almost 4 months, and it's plotted below, along with a 5-point moving average. The most notable feature of the graph is a the drop in benchmark time at about the middle. Sure enough, if you look at the PHP repository, you will see that a set of changes to improve PHP performance were merged on July 29: changes submitted by our very own Anton Blanchard.5

Docker pain points

Docker provides a vastly improved experience over previous solutions, but there are still a few pain points. For example:

-

Docker was apparently written by people who had no concept that platforms other than x86 exist. This leads to major issues for cross-architectural setups. For instance, Docker identifies images by a name and a revision. For example,

ubuntuis the name of an image, and15.04is a revision. There's no ability to specify an architecture. So, how you do specify that you want, say, a 64-bit, little-endian PowerPC build of an image versus an x86 build? There have been a couple of approaches, both of which are pretty bad. You could name the image differently: sayubuntu_ppc64le. You can also just cheat and override theubuntuname with an architecture specific version. Both of these break some assumptions in the Docker ecosystem and are a pain to work with. -

Image building is incredibly inflexible. If you have one system that requires a proxy, and one that does not, you need different Dockerfiles. As far as I can tell, there are no simple ways to hook in any changes between systems into a generic Dockerfile. This is largely by design, but it's still really annoying when you have one system behind a firewall and one system out on the public cloud (as I do in the PHP 7 setup).

-

Visibility into a Docker server is poor. You end up with lots of different, anonymous images and dead containers, and you end up needing scripts to clean them up. It's not clear what Docker puts on your file system, or where, or how to interact with it.

-

Docker is still using reasonably new technologies. This leads to occasional weird, obscure and difficult to debug issues.6

Final words

Docker provides me with a lot of useful tools in software development: both in terms of building and testing. Making use of it requires a certain amount of careful design thought, but when applied thoughtfully it can make life significantly easier.

-

There's some debate about how much stuff from the OS installation you should be using. You need to have key dynamic libraries available, but I would argue that you shouldn't be running long running processes other than your application. You shouldn't, for example, be running a SSH daemon in your container. (The one exception is that you must handle orphaned child processes appropriately: see https://blog.phusion.nl/2015/01/20/docker-and-the-pid-1-zombie-reaping-problem/) Considerations like debugging and monitoring the health of docker containers mean that this point of view is not universally shared. ↩

-

Why not simply make them read only? You may be surprised at how many things break when running on a read-only file system. Things like logs and temporary files are common issues. ↩

-

It is, however, easier to escape a Docker container than a VM. In Docker, an untrusted executable only needs a kernel exploit to get to root on the host, whereas in a VM you need a guest-to-host vulnerability, which are much rarer. ↩

-

Anyone can upload an image, so this does require running untrusted code from the Internet. Sadly, this is a distinctly retrograde step when compared to the process of installing binary packages in distros, which are all signed by a distro's private key. ↩

-

I hit this last week: https://github.com/docker/docker/issues/16256, although maybe that's my fault for running systemd on my laptop. ↩