It started off a regular Wednesday morning when I hear from my desk a colleague

muttering about doubles and their hex representation. "But that doesn't look

right", "How do I read this as a float", and "redacted you're the engineer,

you do it". My interest piqued, I headed over to his desk to enquire about the

great un-solvable mystery of the double and its hex representation. The number

which would consume me for the rest of the morning: 0xc00000001568fba0.

That's a Perfectly Valid hex Number!

I hear you say. And you're right, if we were to treat this as a long it would simply be 13835058055641365408 (or -4611686018068186208 if we assume a signed value). But we happen to know that this particular piece of data which we have printed is supposed to represent a double (-2 to be precise). "Well print it as a double" I hear from the back, and once again we should all know that this can be achieved rather easily by using the %f/%e/%g specifiers in our print statement. The only problem is that in kernel land (where we use printk) we are limited to printing fixed point numbers, hence why our only easy option was to print our double in it's raw hex format.

This is the point where we all think back to that university course where number representations were covered in depth, and terms like 'mantissa' and 'exponent' surface in our minds. Of course as we rack our brains we realise there's no way that we're going to remember exactly how a double is represented and bring up the IEEE 754 Wikipedia page.

What is a Double?

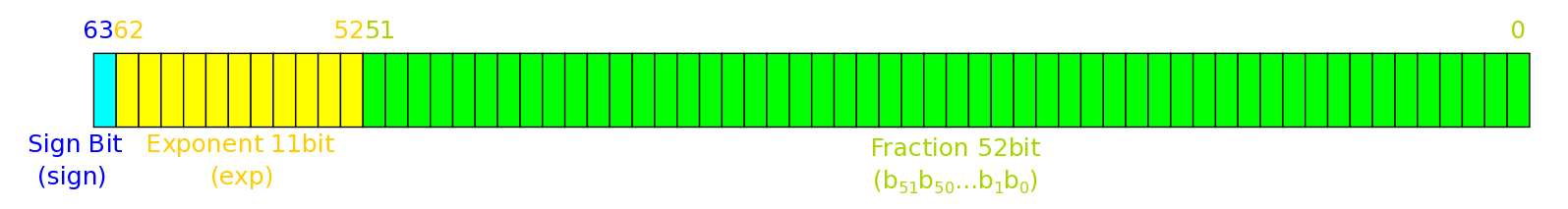

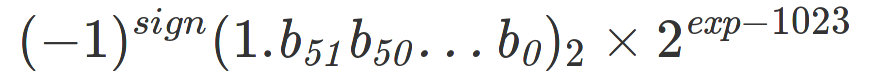

Taking a step back for a second, a double (or a double-precision floating-point) is a number format used to represent floating-point numbers (those with a decimal component). They are made up of a sign bit, an exponent and a fraction (or mantissa):

Where the number they represent is defined by:

So this means that a 1 in the MSB (sign bit) represents a negative number, and we have some decimal component (the fraction) which we multiply by some power of 2 (as determined by the exponent) to get our value.

Alright, so what's 0xc00000001568fba0?

The reason we're all here to be begin with, so what's 0xc00000001568fba0 if we treat it as a double? We can first split it into the three components:

0xc00000001568fba0:

Sign bit: 1 -> Negative

Exponent: 0x400 -> 2(1024 - 1023)

Fraction: 0x1568fba0 -> 1.something

And then use the formula above to get our number:

(-1)1 x 1.something x 2(1024 - 1023)

But there's a much easier way! Just write ourselves a little program in userspace (where we are capable of printing floats) and we can save ourselves most of the trouble.

#include <stdio.h>

void main(void)

{

long val = 0xc00000001568fba0;

printf("val: %lf\n", *((double *) &val));

}

So all we're doing is taking our hex value and storing it in a long (val), then getting a pointer to val, casting it to a double pointer, and dereferencing it and printing it as a float. Drum Roll And the answer is?

"val: -2.000000"

"Wait a minute, that doesn't quite sound right". You're right, it does seem a bit strange that this is exactly -2. Well it may be that we are not printing enough decimal places to see the full result, so update our print statement to:

printf("val: %.64lf\n", *((double *) &val));

And now we get:

"val: -2.0000001595175973534423974342644214630126953125000000"

Much better... But still where did this number come from and why wasn't it the -2 that we were expecting?

Kernel Pointers

At this point suspicions had been raised that what was being printed by my colleague was not what he expected and that this was in fact a Kernel pointer. How do you know? Lets take a step back for a second...

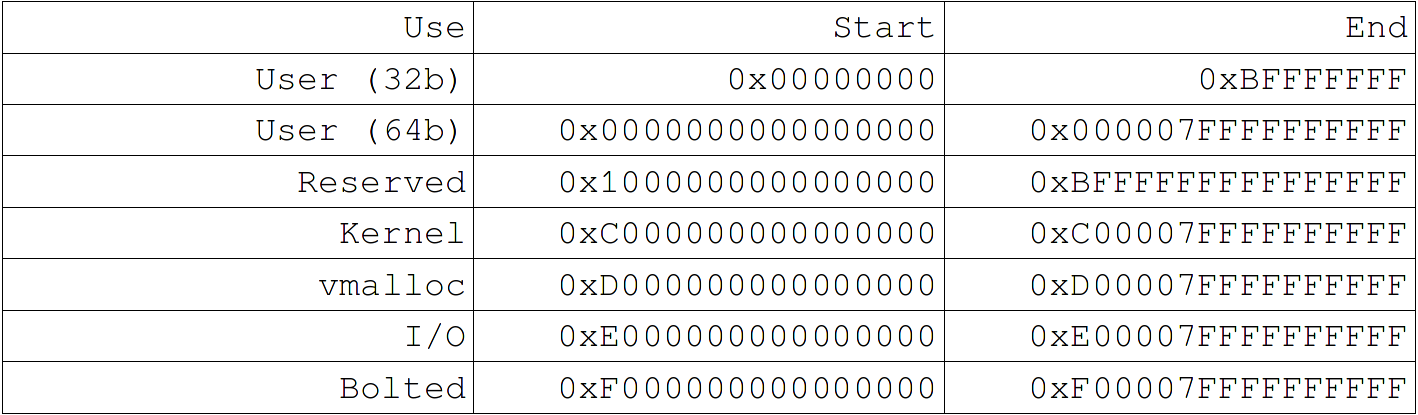

In the PowerPC architecture, the address space which can be seen by an application is known as the effective address space. We can take this and translate it into a virtual address which when mapped through the HPT (hash page table) gives us a real address (or the hardware memory address).

The effective address space is divided into 5 regions:

As you may notice, Kernel addresses begin with 0xc. This has the advantage that we can map a virtual address without the need for a table by simply masking the top nibble.

Thus it would be reasonable to assume that our value (0xc00000001568fba0) was indeed a pointer to a Kernel address (and further code investigation confirmed this).

But What is -2 as a Double in hex?

Well lets modify the above program and find out:

include <stdio.h>

void main(void)

{

double val = -2;

printf("val: 0x%lx\n", *((long *) &val));

}

Result?

"val: 0xc000000000000000"

Now that sounds much better. Lets take a closer look:

0xc000000000000000:

Sign Bit: 1 -> Negative

Exponent: 0x400 -> 2(1024 - 1023)

Fraction: 0x0 -> Zero

So if you remember from above, we have:

(-1)1 x 1.0 x 2(1024 - 1023) = -2

What about -1? -3?

-1:

0xbff0000000000000:

Sign Bit: 1 -> Negative

Exponent: 0x3ff -> 2(1023 - 1023)

Fraction: 0x0 -> Zero

(-1)1 x 1.0 x 2(1023 - 1023) = -1

-3:

0xc008000000000000:

Sign Bit: 1 -> Negative

Exponent: 0x400 -> 2(1024 - 1023)

Fraction: 0x8000000000000 -> 0.5

(-1)1 x 1.5 x 2(1024 - 1023) = -3

So What Have We Learnt?

Firstly, make sure that what you're printing is what you think you're printing.

Secondly, if it looks like a Kernel pointer then you're probably not printing what you think you're printing.

Thirdly, all Kernel pointers ~= -2 if you treat them as a double.

And Finally, with my morning gone, I can say for certain that if we treat it as a double, 0xc00000001568fba0 = -2.0000001595175973534423974342644214630126953125.