What is SROP?

Sigreturn Oriented Programming - a general technique that can be used as an exploit, or as a backdoor to exploit another vulnerability.

Okay, but what is it?

Yeah... Let me take you through some relevant background info, where I skimp on the details and give you the general picture.

In Linux, software interrupts are called signals. More about signals here! Generally a signal will convey some information from the kernel and so most signals will have a specific signal handler (some code that deals with the signal) setup.

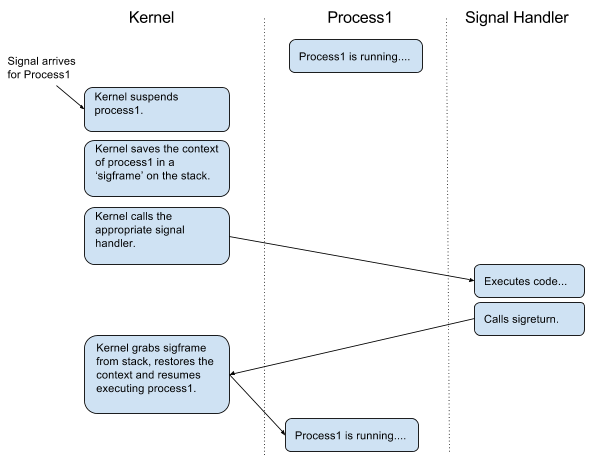

Signals are asynchronous - ie they can be sent to a process/program at anytime. When a signal arrives for a process, the kernel suspends the process. The kernel then saves the 'context' of the process - all the general purpose registers (GPRs), the stack pointer, the next-instruction pointer etc - into a structure called a 'sigframe'. The sigframe is stored on the stack, and then the kernel runs the signal handler. At the very end of the signal handler, it calls a special system call called 'sigreturn' - indicating to the kernel that the signal has been dealt with. The kernel then grabs the sigframe from the stack, restores the process's context and resumes the execution of the process.

This is the rough mental picture you should have:

Okay... but you still haven't explained what SROP is..?

Well, if you insist...

The above process was designed so that the kernel does not need to keep track of what signals it has delivered. The kernel assumes that the sigframe it takes off the stack was legitimately put there by the kernel because of a signal. This is where we can trick the kernel!

If we can construct a fake sigframe, put it on the stack, and call sigreturn, the kernel will assume that the sigframe is one it put there before and will load the contents of the fake context into the CPU's registers and 'resume' execution from where the fake sigframe tells it to. And that is what SROP is!

Well that sounds cool, show me!

Firstly we have to set up a (valid) sigframe:

By valid sigframe, I mean a sigframe that the kernel will not reject. Luckily most architectures only examine a few parts of the sigframe to determine the validity of it. Unluckily, you will have to dive into the source code to find out which parts of the sigframe you need to set up for your architecture. Have a look in the function which deals with the syscall sigreturn (probably something like sys_sigreturn() ).

For a real time signal on a little endian powerpc 64bit machine, the sigframe looks something like this:

struct rt_sigframe {

struct ucontext uc;

unsigned long _unused[2];

unsigned int tramp[TRAMP_SIZE];

struct siginfo __user *pinfo;

void __user *puc;

struct siginfo info;

unsigned long user_cookie;

/* New 64 bit little-endian ABI allows redzone of 512 bytes below sp */

char abigap[USER_REDZONE_SIZE];

} __attribute__ ((aligned (16)));

The most important part of the sigframe is the context or ucontext as this contains all the register values that will be written into the CPU's registers when the kernel loads in the sigframe. To minimise potential issues we can copy valid values from the current GPRs into our fake ucontext:

register unsigned long r1 asm("r1");

register unsigned long r13 asm("r13");

struct ucontext ctx = { 0 };

/* We need a system thread id so copy the one from this process */

ctx.uc_mcontext.gp_regs[PT_R13] = r13;

/* Set the context's stack pointer to where the current stack pointer is pointing */

ctx.uc_mcontext.gp_regs[PT_R1] = r1;

We also need to tell the kernel where to resume execution from. As this is just a test to see if we can successfully get the kernel to resume execution from a fake sigframe we will just point it to a function that prints out some text.

/* Set the next instruction pointer (NIP) to the code that we want executed */

ctx.uc_mcontext.gp_regs[PT_NIP] = (unsigned long) test_function;

For some reason the sys_rt_sigreturn() on little endian powerpc 64bit checks the endianess bit of the ucontext's MSR register, so we need to set that:

/* Set MSR bit if LE */

ctx.uc_mcontext.gp_regs[PT_MSR] = 0x01;

Fun fact: not doing this or setting it to 0 results in the CPU switching from little endian to big endian! For a powerpc machine sys_rt_sigreturn() only examines ucontext, so we do not need to set up a full sigframe.

Secondly we have to put it on the stack:

/* Set current stack pointer to our fake context */

r1 = (unsigned long) &ctx;

Thirdly, we call sigreturn:

/* Syscall - NR_rt_sigreturn */

asm("li 0, 172\n");

asm("sc\n");

When the kernel receives the sigreturn call, it looks at the userspace stack pointer for the ucontext and loads this in. As we have put valid values in the ucontext, the kernel assumes that this is a valid sigframe that it set up earlier and loads the contents of the ucontext in the CPU's registers "and resumes" execution of the process from the address we pointed the NIP to.

Obviously, you need something worth executing at this address, but sadly that next part is not in my job description. This is a nice gateway into the kernel though and would pair nicely with another kernel vulnerability. If you are interested in some more in depth examples, have a read of this paper.

So how can we mitigate this?

Well, I'm glad you asked. We need some way of distinguishing between sigframes that were put there legitimately by the kernel and 'fake' sigframes. The current idea that is being thrown around is cookies, and you can see the x86 discussion here.

The proposed solution is to give every sighand struct a randomly generated value. When the kernel constructs a sigframe for a process, it stores a 'cookie' with the sigframe. The cookie is a hash of the cookie's location and the random value stored in the sighand struct for the process. When the kernel receives a sigreturn, it hashes the location where the cookie should be with the randomly generated number in sighand struct - if this matches the cookie, the cookie is zeroed, the sigframe is valid and the kernel will restore this context. If the cookies do not match, the sigframe is not restored.

Potential issues:

- Multithreading: Originally the random number was suggested to be stored in the task struct. However, this would break multi-threaded applications as every thread has its own task struct. As the sighand struct is shared by threads, this should not adversely affect multithreaded applications.

- Cookie location: At first I put the cookie on top of the sigframe. However some code in userspace assumed that all the space between the signal handler and the sigframe was essentially up for grabs and would zero the cookie before I could read the cookie value. Putting the cookie below the sigframe was also a no-go due to the ABI-gap (a gap below the stack pointer that signal code cannot touch) being a part of the sigframe. Putting the cookie inside the sigframe, just above the ABI gap has been fine with all the tests I have run so far!

- Movement of sigframe: If you move the sigframe on the stack, the cookie value will no longer be valid... I don't think that this is something that you should be doing, and have not yet come across a scenario that does this.

For a more in-depth explanation of SROP, click here.