Every once in a while I read papers or articles. Previously, I've just read them myself, but I was wondering if there were more useful things I could do beyond that. So I've written up a summary and my thoughts on an article I read - let me know if it's useful!

I recently read Curing the Vulnerable Parser: Design Patterns for Secure Input Handling (Bratus, et al; USENIX ;login: Spring 2017). It's not a formal academic paper but an article in the Usenix magazine, so it doesn't have a formal abstract I can quote, but in short it takes the long history of parser and parsing vulnerabilities and uses that as a springboard to talk about how you could design better ones. It introduces a toolkit based on that design for more safely parsing some binary formats.

Background

It's worth noting early on that this comes out of the LangSec crowd. They have a pretty strong underpinning philosophy:

The Language-theoretic approach (LANGSEC) regards the Internet insecurity epidemic as a consequence of ad hoc programming of input handling at all layers of network stacks, and in other kinds of software stacks. LANGSEC posits that the only path to trustworthy software that takes untrusted inputs is treating all valid or expected inputs as a formal language, and the respective input-handling routines as a recognizer for that language. The recognition must be feasible, and the recognizer must match the language in required computation power.

A big theme in this article is predictability:

Trustworthy input is input with predictable effects. The goal of input-checking is being able to predict the input’s effects on the rest of your program.

This seems sensible enough at first, but leads to some questionable assertions, such as:

Safety is predictability. When it's impossible to predict what the effects of the input will be (however valid), there is no safety.

They follow this with an example of Ethereum contracts stealing money from the DAO. The example is compelling enough, but again comes with a very strong assertion about the impossibility of securing a language virtual machine:

From the viewpoint of language-theoretic security, a catastrophic exploit in Ethereum was only a matter of time: one can only find out what such programs do by running them. By then it is too late.

I'm not sure that (a) I buy the assertions, or that (b) they provide a useful way to deal with the world as we find it.

Is this even correct?

You can tease out 2 contentions in the first part of the article:

- there should be a formal language that describes the data, and

- this language should be as simple as possible, ideally being regular and context-free.

Neither of these are bad ideas - in fact they're both good ideas - but I don't know that I draw the same links between them and security.

Consider PostScript as a possible counter-example. It's a Turing-complete language, so it absolutely cannot have predictable results. It has a well documented specification and executes in a restricted virtual machine. So let's say that it satisfies only the first plank of their argument.

I'd say that PostScript has a good security record, despite being Turing complete. PostScript has been around since 1985 and apart from the recent bugs in GhostScript, it doesn't have a long history of bugs and exploits. Maybe this just because no-one has really looked, or maybe it is possible to have reasonably safe complex languages by restricting the execution environment, as PostScript consciously and deliberately does.

Indeed, if you consider the recent spate of GhostScript bugs, perhaps some may be avoided by stricter compliance with a formal language specification. However, most seem to me to arise from the desirability of implementing some of the PostScript functionality in PostScript itself, and some of the GhostScript-specific, stupendously powerful operators exposed to the language to enable this. The bugs involve tricks to allow a user to get access to these operators. A non-Turing-complete language may be sufficient to prevent these attacks, but it is not necessary: just not doing this sort of meta-programming with such dangerous operators would also have worked. Storing the true values of the security state outside of a language-accessible object would also be good.

Is this a useful way to deal with the world as we find it?

My main problem with the general LangSec approach that this article takes is this: to get to their desired world, we need to rewrite a bunch of things with entirely different language foundations. The article talks about HTML and PDFs as examples of unsafe formats, but I cannot imagine the sudden wholesale replacement of either of these - although I would love to be proven wrong.

Can we get even part of the way with existing standards? Kinda-sorta, but mostly no, and to the authors' credit, they are open about this. They argue that formal definition parsing the language should be the "most restrictive input definition" - they specifically require you to "give up attempting to accept arbitrarily complex data", and call for "subsetting of many protocols, formats, encodings and command languages, including eliminating unneeded variability and introducing determinism and static values".

No doubt we would be in a better place if people took up these ideas for future programs. However, for our current set of programs and use cases, this is probably not tractable in any meaningful way.

The rest of the paper

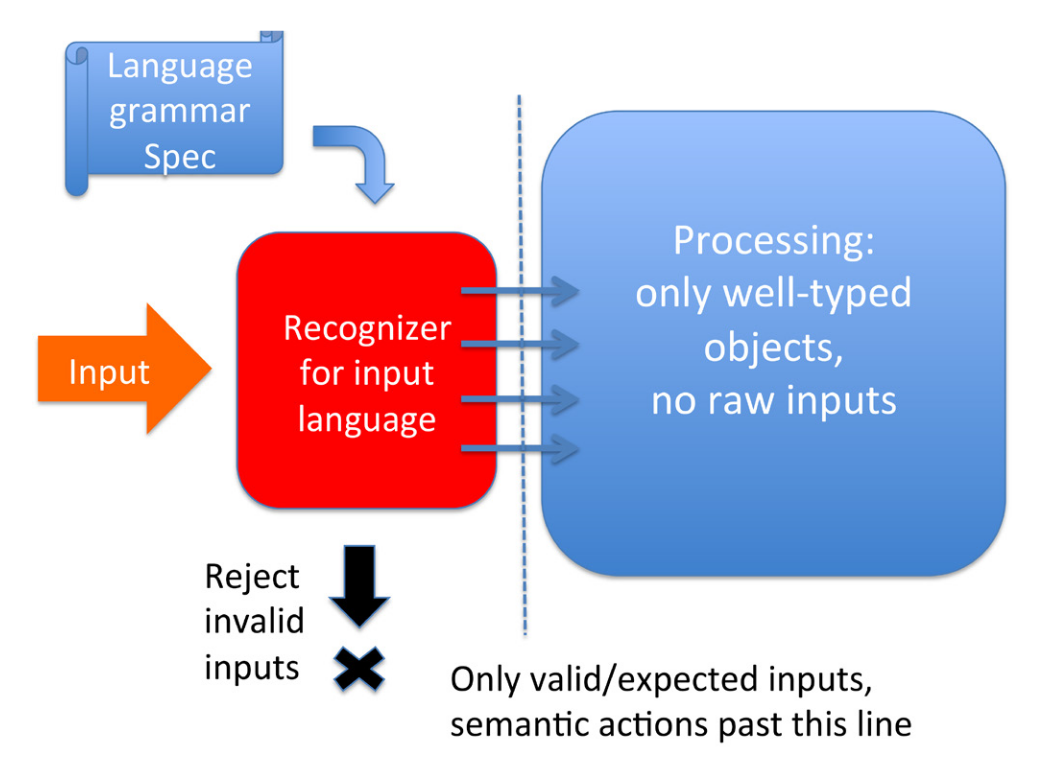

The rest of the paper is reasonably interesting. Their general theory is that you should build your parsers based on a formal definition of a language, and that the parser should convert the input data to a set of objects, and then your business logic should deal with those objects. This is the 'recognizer pattern', and is illustrated below:

In short, the article is full of great ideas if you happen to be parsing a simple language, or are designing not just a parser but a full language ecosystem. They do also provide a binary parser toolkit that might be helpful if you are parsing a binary format that can be expressed with a parser combinator.

Overall, however, I think the burden of maintaining old systems is such that a security paradigm that relies on new code is pretty unlikely, and one that relies on new languages is fatally doomed from the outset. New systems should take up these ideas, yes. But I'd really like to see people grappling with how to deal with the complex and irregular languages that we're stuck with (HTML, PDF, etc) in secure ways.